Okay, so I’m going to move on to what I’m supposed to be working on and writing about: the boat.

|

| Spirit, not at sea |

A boat under progress is not very photogenic. Note the pine needles, the antifreeze bottles full of tap water used as weights, the carelessly hung rags and ratchet straps and cleaning accoutrements. Doing boat work in the middle of a pine forest is likewise not very easy. Every day starts with clearing the pine needles from whatever needs to be worked on.

I am resentful and angry about boat work. I didn’t want to buy a boat. I was happy with my little farmstead and office in Maine, and I was burned so badly by the last boat that I didn’t think I could ever trust a new boat. I remember how my heart broke last time.

I remember that the day-to-day reality of boat life involves mammoth amounts of brute physical labor. Cleaning. Plumbing maintenance. Cooking with limited ingredients and space.

And still I want to sail, not because I actually want to sail, but because I am still hungry for adventure, for travel, because my peripatetic urge is never satisfied. I want to cross an ocean. I want to drop luffing sails in the harbor of the Azores. I want to traverse the Suez and Panama Canals, cruise the Mediterranean, round the great Capes, cross from Newfoundland to Ireland. These are things I hunger after.

In Stephen King’s “On Writing” he says, of his wife:

In the end it was Tabby who cast the deciding vote, as she so often has at crucial moments in my life. I'd like to think I've done the same for her from time to time, because it seems to me that one of the things marriage is about is casting the tie-breaking vote when you just can't decide what you should do next.

As with a writing life, what really matters in cruising is who you choose to do it with. I know, from meeting many grounded sailors, that what most often gets in the way of achieving a sailing dream is not hurricanes, or pirates, or broaching whales—but unwilling partners. Your feet get tied up to the ground, not by roots, but by people.

And now I am one of those people.

I believe that the thing that entranced so many [elderly, male, ex-] sailors about the voyage of sailing vessel Secret is that I—the nubile female blog heroine—wanted so desperately to keep sailing and my partner did not.

This indecision has been a problem for a long time between us.

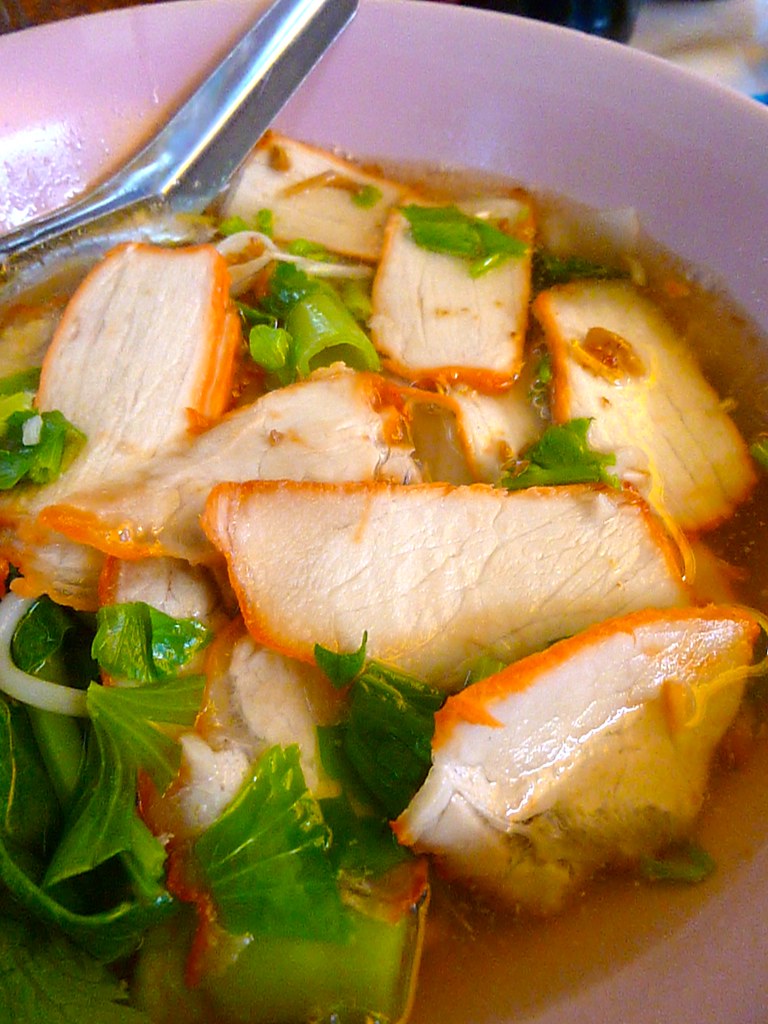

A Wharram catamaran sings her siren song for me, at her port in Phuket. So does the idea of a beach camping cruise along the Mexican coast. The Continental Divide Trail. Cyprus, where my grandfather is from. Bangkok, always. Not to mention the best gift K. ever gave me, a writing room. Again, King: “Like your bedroom, your writing room should be private, a place where you go to dream.”

Also, famously, he said: “Write with the door closed.”

Virginia Woolf, much more famously, said: “All I could do was to offer you an opinion upon one minor point — a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction; and that, as you will see, leaves the great problem of the true nature of woman and the true nature of fiction unsolved.”

Worst of all, I remember that a boat has no door that closes.

[Well, there’s a head, smelling of holding tank, but certainly not a private writing room, not a place where you go to dream.]

I’ve been reading boat blogs, trying to get a handle again on this life that I’m not sure I’ve quite chosen again, and all of the sunniest cruising and travel blogs open with

whimsical romantic stories of carpenters meeting bookworms, or

spur-of-the-moment decisions over beer and pizza, or one partner convincing the other that what they really needed was a sailboat:

“I have long had a dream of going cruising in a sailboat and have gradually lured Mark into this dream. His response has ranged from all smiles to the rare bout of kicking and screaming, but he finally agreed to purchase a boat a year ago.” —

s/v Groovy“In May 2011 Tammara and I made the decision to purchase a sailboat to sail and live on and eventually take her down the west coast… It is our dream to one day voyage across oceans to distant and foreign lands. We hope to achieve this with our new boat.” —

s/v Lynn-Marie“Have you ever dreamt of running away to live on a tropical island, spending your days basking in the warm sunshine while sipping piña coladas? We have. In fact, our dream included running away to live on a sailboat in the tropics, even though when we started we had never even sailed before! Zero to Cruising is the story of how we took that dream and made it a reality. Follow along... you can do it too!” --

s/v Zero to Cruising“Our goal is to share meaningful thoughts on simple living, to help sailors with life aboard, and to inspire others to chase their own creative dream through honest and uplifting writing.” —

s/v Sailing SimplicityI find that so much of actual life aboard—which is constant interpersonal decision-making—gets left out of these blogs.

Then there’s the much more honest

s/v More Joy Everywhere, posting shortly before

deciding to sell:

“These blogs are all written by people who are younger and prettier and smarter and more creative than we are. They fix engines, install solar panels, sew cushions, grow sprouts, revarnish their teak, and understand how their systems work. In their spare time, they sketch, make jewelry, write poetry, play the banjo, kayak, scuba dive, take fabulous underwater pictures, and never watch television.”

It’s easy to paint a romantic vision of life aboard—all sunsets and dolphins and glowing teak and tranquil anchorages. It’s easy, when one is parsing a life a post or two at a time, to focus only on the beautiful things. It’s why everyone, in our age of social networks, has a chronic diagnosis of

FOMO. We see everyone else’s gorgeous handmade children’s crafts, or snapshots of family vacations—we don’t see the dirty dishes, the arguments, the days spent in front of the television, the exhaustion, the chaos.

Some of the most inspirational and optimistic blogs drift slowly off into the ether with no explanation as to what exactly happened to the pina colada dream. Some others, as with the second example above, have posts stop soon before the

Sailboat Listing appears. [

Click here for a great collection of blog posts about cruisers who decide to quit.]

You’ll know, if you’ve read for a long time, that I love to write about being covered in poison oak, or boat poop explosions, or frigid Maine winters. It’s the part of life that’s interesting to me. What interests me about life—what interests me about travel—what interests me in literature and film and art—are the things that are difficult, the things that are hard, the challenges remaining to be overcome.

I know that I want to write, as I’ve always known, but as I said to Karl, when we first met: I can do that anywhere.

He asked me what I did for a living, what I was, and I said: a bum.

He asked me to live aboard a boat with him, on our first date, and I said, with no hesitation: yes.

Sailing is a full-time job. Boat work is a full-time job. Writing, too, is a full-time job. So what

then? I wrestle what time I can from the ether, and I use it to put

words on paper, or onto a screen, or I stare into space and avoid

putting words on paper or onscreen. I miss my grandmother’s

typewriter. I miss my office and my desk and my view of the drained

beaver pond. I miss my literary dog and cat.

Can I really do it anywhere? I guess we’ll find out.

And I guess, dear reader, you can always trust me, yours truly, to delve my hands deep down into the dirty painful nitty gritty of life, can you not? I commit to you that I’ll continue to explore the dark side of life afoot or a-sail—at least a sunny post or two a month at a time.